Notation#

Names and defs#

The following abbreviations and symbols are commonly associated with statistical methodologies like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Principal Component Regression (PCR).

PCA (Principal Component Analysis):#

PCA is a dimensionality reduction technique that’s often used to reduce the number of variables in a dataset while retaining most of the original variability. It does this by projecting the original data into a new coordinate system defined by the principal components.

\(X\):#

This typically represents the original data matrix with rows as observations (e.g., individuals) and columns as variables (e.g., features or measurements).

Each entry \(X_{ij}\) represents the measurement of the \(j^{th}\) variable for the \(i^{th}\) observation.

\(\Gamma\): (Gamma)#

Matrix of eigenvectors of the covariance matrix.

Note: \(\Gamma\) is orthogonal (\(\Gamma^T = \Gamma^{-1}\)).

vector =PCX$rotation

The columns of \(\Gamma\) are the eigenvectors of the covariance matrix of \(X\). Each column (eigenvector) points in the direction of a principal component. These eigenvectors are also often referred to as “loadings.”

In other words, \(\Gamma\) provides the weights or coefficients that transform the original data \(X\) into its principal components \(Y\). If \(X\) has \(p\) predictors, then \(\Gamma\) will be a \(p \times p\) matrix, where the first column is the loading vector for PC1, the second column is the loading vector for PC2, and so on.

The matrix of eigenvectors, denoted as \(\Gamma\), contains the principal directions of the dataset. Each column of \(\Gamma\) represents an eigenvector, ordered by the corresponding eigenvalue in descending order.

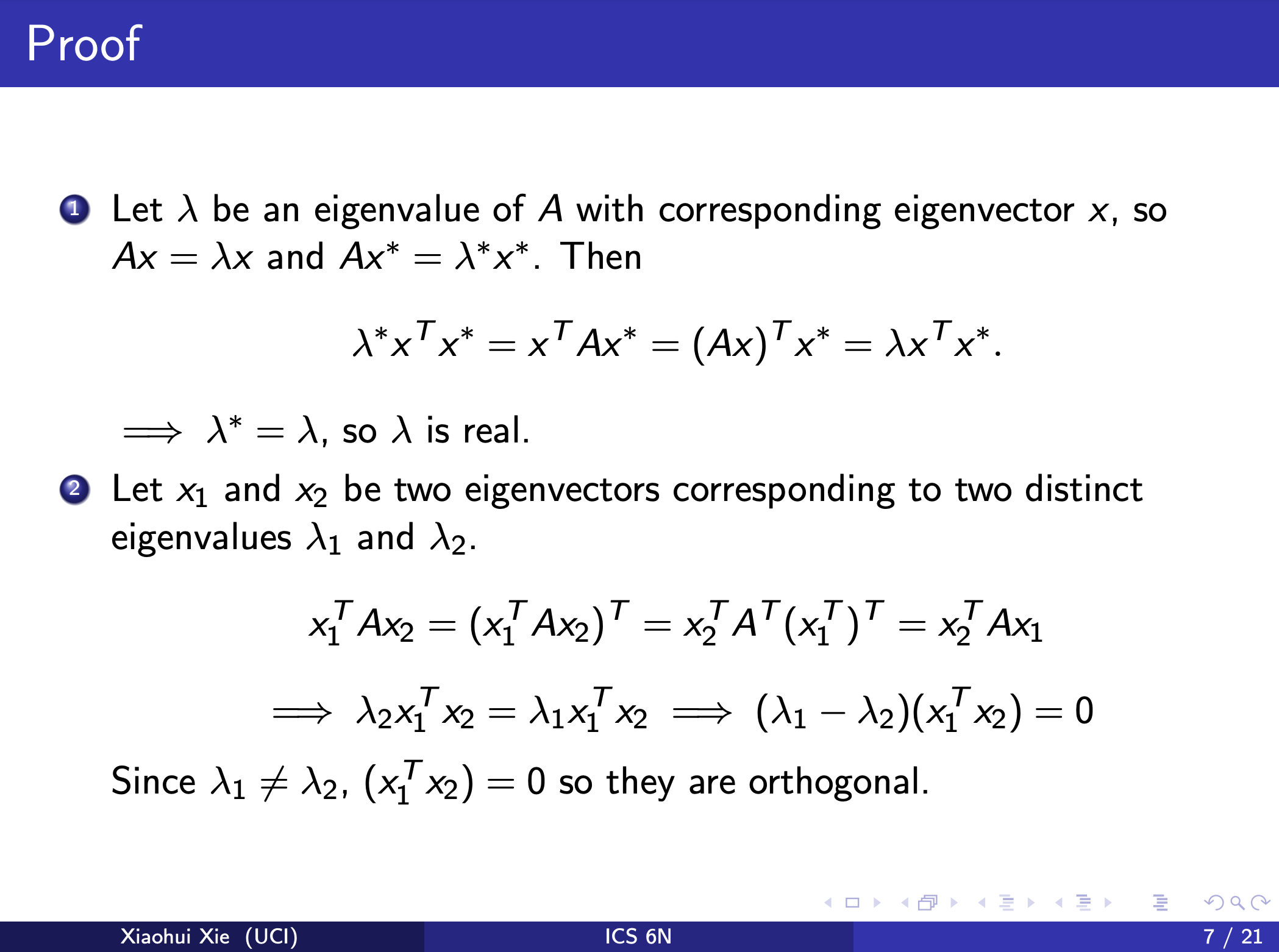

orthogonality#

Why orthogonal?

Symmetric Matrix: A covariance matrix is always symmetric since \( \text{Cov}(X, Y) = \text{Cov}(Y, X) \). The covariance between any two variables \( X \) and \( Y \) is the same, regardless of the order.

Real Eigenvalues: For any symmetric matrix, the eigenvalues are always real numbers (not complex). This is a property of symmetric matrices that stems from the fact that a symmetric matrix equals its own transpose.

Orthogonal Eigenvectors: When a matrix is symmetric, its eigenvectors corresponding to different eigenvalues are orthogonal to each other. This means that if you take any two eigenvectors from a symmetric matrix, their dot product will be zero, indicating that they are perpendicular in the space spanned by the data.

Spectral Theorem: The spectral theorem for symmetric matrices states that a real symmetric matrix can be diagonalized by an orthogonal matrix. In other words, if \( A \) is a symmetric matrix, there exists an orthogonal matrix \( Q \) such that \( Q^T A Q = D \), where \( D \) is a diagonal matrix containing the eigenvalues of \( A \) and \( Q \) contains the eigenvectors of \( A \).

Eigendecomposition: The eigendecomposition of a covariance matrix \( \Sigma \) is given by \( \Sigma = \Gamma \Lambda \Gamma^T \), where \( \Lambda \) is a diagonal matrix whose diagonal elements are the eigenvalues, and \( \Gamma \) is the orthogonal matrix whose columns are the eigenvectors. The transpose of an orthogonal matrix is also its inverse, which means \( \Gamma^T \Gamma = I \), where \( I \) is the identity matrix.

The orthogonality of eigenvectors is a crucial property in principal component analysis (PCA) and other multivariate techniques because it ensures that the new axes (principal components) are uncorrelated with each other, which is one of the goals of these methods—to transform correlated variables into a set of uncorrelated variables.

Why are principal components in PCA (eigenvectors of the covariance matrix) mutually orthogonal?

ICS 6N Computational Linear Algebra Symmetric Matrices and Orthogonal Diagonalization

The eigenspaces are mutually orthogonal: If λ1 = λ2 are two distinct eigenvalues, then their corresponding eigenvectors v1, v2 are orthogonal.

What if \(\lambda = \mu\) (equal eigenvalues)?

Spectrum Theorem is the solution!

If \( \lambda = \mu \), that means we are dealing with a repeated eigenvalue (also known as a degenerate eigenvalue) in the context of the covariance matrix for PCA.

In the case of a repeated eigenvalue \( \lambda \), the corresponding eigenspace (the space spanned by all the eigenvectors associated with \( \lambda \)) might be multidimensional, i.e., there might be more than one linearly independent eigenvector corresponding to the eigenvalue \( \lambda \).

For a symmetric matrix (like the covariance matrix in PCA), the Spectral Theorem assures us that even with repeated eigenvalues, we can still find an orthogonal basis for each eigenspace. This means that within the subspace of eigenvectors corresponding to the repeated eigenvalue, we can select or construct eigenvectors that are orthogonal to each other.

Here’s why this is important for PCA:

PCA Seeks Orthogonality: In PCA, we look for orthogonal axes (principal components) that represent different dimensions of variance in the data. If we had non-orthogonal axes, they would not represent independent dimensions of variance.

Interpretability: Orthogonal eigenvectors lead to principal components that are uncorrelated with each other, which makes them easier to interpret in terms of the variance of the data they explain.

Stability and Uniqueness: While the choice of orthogonal eigenvectors within a repeated eigenvalue is not unique (there are infinitely many sets of orthogonal vectors within a subspace), the fact that they are orthogonal lends a form of stability to the PCA results in that each of the selected vectors will still describe a unique aspect of the variance in the data.

When implementing PCA:

Numerical Algorithms: Computational routines (like those in LAPACK or other linear algebra libraries) that are used to find the eigenvectors of a symmetric matrix automatically take care of finding orthogonal eigenvectors, even in the case of repeated eigenvalues.

SVD Approach: When using Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) to perform PCA, the issue of repeated eigenvalues does not directly arise. SVD decomposes the data matrix into orthogonal matrices, ensuring the orthogonality of the components.

So, in practice, even when \( \lambda = \mu \), PCA implementations ensure that the resulting principal components are orthogonal and thus can be used effectively for dimensionality reduction, feature extraction, or data visualization purposes.

The Spectral Theorem is a fundamental result in linear algebra that provides the conditions under which a matrix can be diagonalized through a basis of eigenvectors. In its most general form applicable to symmetric matrices, the theorem states:

Spectral Theorem for Symmetric Matrices: Every real symmetric matrix \( A \) can be diagonalized by an orthogonal matrix. That is, for any real symmetric matrix \( A \), there exists an orthogonal matrix \( Q \) and a diagonal matrix \( D \) such that

Here’s what this means in more detail:

Real Symmetric Matrix: The matrix \( A \) is symmetric if \( A = A^T \), and all of its entries are real numbers.

Orthogonal Matrix: The matrix \( Q \) is orthogonal if its columns are orthonormal eigenvectors of \( A \), meaning that \( Q^TQ = QQ^T = I \), where \( I \) is the identity matrix. The orthonormality condition implies that each eigenvector is unit length, and any pair of different eigenvectors are orthogonal to each other.

Diagonal Matrix: The diagonal matrix \( D \) contains the eigenvalues of \( A \) along its diagonal, and these eigenvalues are real numbers because \( A \) is symmetric.

Diagonalization: To say that \( A \) can be diagonalized means that there is a basis for the vector space consisting entirely of eigenvectors of \( A \), and when \( A \) is represented in this basis, it takes on a diagonal form.

This theorem is particularly powerful for several reasons:

It guarantees that eigenvalues of a real symmetric matrix are always real, even though eigenvalues of non-symmetric matrices can be complex.

It provides an orthogonal set of eigenvectors for symmetric matrices, which is crucial for many applications in mathematics, physics, engineering, statistics, and machine learning, including PCA.

It implies that quadratic forms associated with symmetric matrices can be easily studied by considering their diagonal form, which simplifies understanding their topography (e.g., identifying maxima, minima, and saddle points).

In the context of PCA, the Spectral Theorem ensures that we can find a set of orthogonal principal components, even if some eigenvalues are repeated. These principal components can be used to describe the variance in the dataset with uncorrelated features, simplifying both the geometry and the statistics of high-dimensional data.

\(Y\):#

Matrix of scores on PC / Data after PCA

Y=PCX$X

Y[,1] # first PC

Y[,2] # second PC

When you project the original data \(X\) onto the principal components (or eigenvectors), you get a new data representation, \(Y\). Here, \(Y\) contains the scores of the observations on the principal components. The first column of \(Y\) contains the scores for PC1, the second column has the scores for PC2, and so on.

Similarly, as Γ is orthogonal:

\(Z\):#

Predicted outcome variable, based on the regression model.

In the equation \(Z = \beta^T X + \epsilon\), \(Z\) is the predicted value, \(\beta^T\) is the transpose of the coefficient vector, and \(\epsilon\) is the error term.

\(\Lambda\) (Lambda):#

Diagonal matrix of eigenvalue

This is a diagonal matrix of the variances of the principal components. In PCA, the components are ordered by the amount of variance they explain in the original data. The first principal component explains the most variance, the second explains the next highest amount, and so on. These variances are the eigenvalues of the covariance matrix of \(X\).

\( \lambda_1 \)#

Eigenvalue (variance of PC)

The symbol \( \lambda_1 \) typically refers to the first (and largest) eigenvalue when discussing matrices, especially in the context of Principal Component Analysis (PCA).

In PCA, \( \lambda_1 \) represents the amount of variance explained by the first principal component. The eigenvalues (like \( \lambda_1 \)) are obtained from the covariance (or sometimes correlation) matrix of the dataset.

Here’s a brief overview of how \( \lambda_1 \) is calculated:

Standardize the Data (if needed): Before PCA, it’s common to standardize each variable so they all have a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1. This ensures that all variables are on a comparable scale.

Compute the Covariance Matrix: If \( X \) is the centered data matrix, the sample covariance matrix \( S \) is given by:

\[ S = \frac{1}{n-1} X^T X \]where \( n \) is the number of observations.

Compute Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors of the Covariance Matrix: For the covariance matrix \( S \), we want to find scalars \( \lambda \) (eigenvalues) and vectors \( v \) (eigenvectors) such that:

\[ S v = \lambda v \]There are many algorithms and software packages (like in Python or R) that can compute the eigenvalues and eigenvectors for you.

Order Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors: Once you have all the eigenvalues, you’ll order them from largest to smallest. \( \lambda_1 \) would be the largest eigenvalue, \( \lambda_2 \) would be the second largest, and so on. The eigenvector associated with \( \lambda_1 \) is the first principal component.

As a note, \( \lambda_1 \) (and other eigenvalues) can be interpreted as the amount of variance explained by the corresponding principal component. The ratio \( \lambda_1 \) divided by the sum of all eigenvalues gives the proportion of total variance explained by the first principal component.

\( \Phi\) (Phi)#

Cumulative variance proportion

Here, \( \lambda_j \) represents the eigenvalue (variance) of the \( j \)-th principal component, \( \text{var}(Y_{ij}) \) is the variance explained by the \( j \)-th principal component, \( q \) is the number of components you are summing over (the ones you want to consider), and \( p \) is the total number of components (which is equal to the number of original variables).

The cumulative variance proportion \( \phi_q \) is calculated by summing the variances explained by each of the first \( q \) components and dividing by the total variance. In the context of PCA, this tells us how much of the information (in terms of the total variability) contained in the original data is captured by the first \( q \) principal components.

Here’s what the values mean in terms of \( \phi \):

\( \phi_1 = 0.668 \): The first principal component explains 66.8% of the total variance in the data.

\( \phi_2 = 0.876 \): The first two principal components together explain 87.6% of the total variance.

\( \phi_3 = 0.930 \): The first three principal components explain 93.0% of the total variance.

\( \phi_4 = 0.973 \): The first four principal components explain 97.3% of the total variance.

\( \phi_5 = 0.992 \): The first five principal components explain 99.2% of the total variance.

\( \phi_6 = 1.000 \): All six components together explain 100% of the total variance, which is to be expected as the number of principal components equals the number of original variables.

In practical terms, this cumulative proportion of explained variance is used to decide how many principal components to keep. If a small number of components explain most of the variance, you may choose to ignore the rest, thereby reducing the dimensionality of the data while still retaining most of the information.

–

\( \Sigma \) (Sigma)#

Covariance matrix

Tip

where \(var(Y) = \lambda\)

Why \(Tr( \Sigma ) = \sum \lambda_i\)

In Principal Component Analysis (PCA), the covariance matrix is a key element that captures the variance and correlation between different variables in the dataset. The trace of a matrix, which is the sum of its diagonal elements, has a special significance when it comes to the covariance matrix.

For any square matrix, the trace has an important property: it is equal to the sum of the matrix’s eigenvalues. This is known because the eigenvalues of a matrix represent how much variance there is in the directions of the principal components (in the case of PCA), and the trace represents the total variance of the data.

Here’s why the trace of the covariance matrix equals the sum of its eigenvalues:

Eigenvalue Decomposition: A covariance matrix, which is symmetric, can be decomposed into its eigenvectors and eigenvalues. This is often written as \( \Sigma = Q \Lambda Q^T \), where \( \Sigma \) is the covariance matrix, \( Q \) is the matrix of eigenvectors, and \( \Lambda \) is the diagonal matrix of eigenvalues. The columns of \( Q \) are the principal components of the data.

Trace and Eigenvalues: When you calculate the trace of the covariance matrix \( \Sigma \), you are essentially summing the diagonal elements of \( \Sigma \). If you substitute \( \Sigma \) with \( Q \Lambda Q^T \) and take the trace, you get:

Using the cyclic property of the trace (which allows rearranging the factors in a trace without changing the result, \( \text{tr}(ABC) = \text{tr}(CAB) = \text{tr}(BCA) \)), we get:

Since \( Q \) is an orthogonal matrix (for a covariance matrix, the eigenvectors are orthogonal), \( Q^T Q \) equals the identity matrix \( I \). Thus, the trace simplifies to the trace of \( \Lambda \), which is the sum of the eigenvalues because \( \Lambda \) is a diagonal matrix.

Variance Explanation: Each eigenvalue represents the variance along its corresponding eigenvector (principal component). So, the sum of the eigenvalues is the sum of the variances in each of the principal component directions. Since the trace of the covariance matrix represents the total variance in the data (by summing the variances of each variable), it must be equal to the sum of the eigenvalues.

In summary, the reason the trace of the covariance matrix in PCA equals the sum of its eigenvalues is because the trace is invariant under a change of basis (which is what the eigenvectors provide) and because the trace represents the total variance encapsulated by the eigenvalues. This mathematical property holds not just in PCA, but in linear algebra generally for any square matrix.

Why \(Det(\Sigma) = \Pi \lambda_i \)

The determinant of a matrix is a scalar value that is a function of all the elements of the matrix. For a covariance matrix \( \Sigma \) (which is symmetric and positive semi-definite), the determinant can give us insights into the total variance captured by the matrix and can also be related to the volume of the data it represents in the multi-dimensional space.

When we talk about the determinant of \( \Sigma \) being equal to \( \Lambda \), there’s a bit of clarification needed. \( \Lambda \) here should be understood not as the matrix of eigenvalues but as the product of the eigenvalues, because the determinant of a matrix is equal to the product of its eigenvalues.

Here’s why the determinant of the covariance matrix \( \Sigma \) is equal to the product of its eigenvalues:

Eigenvalue Decomposition: As previously mentioned, a covariance matrix \( \Sigma \) can be decomposed as \( \Sigma = Q \Lambda Q^T \), where \( Q \) is the orthogonal matrix of eigenvectors and \( \Lambda \) is the diagonal matrix of eigenvalues.

Determinant of the Decomposed Matrix: When you take the determinant of \( \Sigma \), you can express it in terms of its decomposition:

Using the property that the determinant of a product of matrices equals the product of their determinants (\( \det(AB) = \det(A) \det(B) \)), we can write:

Since \( Q \) is an orthogonal matrix, its determinant is \( \pm 1 \), and therefore \( \det(Q) \det(Q^T) = (\pm 1)(\pm 1) = 1 \). This simplifies our equation to:

Determinant of the Diagonal Matrix of Eigenvalues: The determinant of a diagonal matrix like \( \Lambda \) is simply the product of its diagonal elements, which are the eigenvalues of \( \Sigma \). Thus, the determinant of \( \Lambda \) is the product of the eigenvalues \( \lambda_i \) of \( \Sigma \):

Therefore:

In this way, the determinant of the covariance matrix \( \Sigma \) is indeed equal to the product of its eigenvalues, not the sum. This product of eigenvalues (or determinant of \( \Sigma \)) gives us a measure of the “spread” or “volume” of the data in the space defined by the principal components. If any of the eigenvalues are zero (or very close to zero), it indicates that the data is lying flat in some dimension, and the determinant will be zero (or very small), reflecting the lower dimensionality of the dataset.

Where:

Diagonal terms \(\sigma_X^2\) represent the variance of the respective random variable \(X\).

Off-diagonal terms \(\sigma_{XY}\) represent the covariance between random variables \(X\) and \(Y\).

Let’s use some arbitrary numbers to fill in this matrix:

In this example:

The variance of \(A\) is 5, of \(B\) is 6, of \(C\) is 7, and of \(D\) is 4.

The covariance between \(A\) and \(B\) is 1, between \(A\) and \(C\) is 0.5, and so on.

Remember, this is just an arbitrary example. In real scenarios, the covariance matrix is derived from data. The matrix is symmetric, so the upper triangle and the lower triangle of the matrix are mirror images of each other.

features of the covariance matrix

Symmetry: A covariance matrix is always symmetric. This is because the covariance between variable \(i\) and variable \(j\) is the same as the covariance between variable \(j\) and variable \(i\). Hence, \(cov(X_i, X_j) = cov(X_j, X_i)\).

Positive Semi-definite: A covariance matrix is always positive semi-definite. This means that for any non-zero column vector \(z\) of appropriate dimensions, the quadratic form \(z^T \Sigma z\) will always be non-negative.

Diagonal Elements are Variances: The diagonal entries of a covariance matrix are always variances. Hence, they are always non-negative.

Eigenvalue Decomposition: A covariance matrix can be decomposed into its eigenvectors and eigenvalues. This decomposition has a special property: the eigenvectors are orthogonal to each other. When we do this decomposition:

\( \Sigma = Q\Lambda Q^T \)

Here, \(Q\) is a matrix of the eigenvectors (which are orthogonal, and if normalized, orthonormal) and \(\Lambda\) is a diagonal matrix with eigenvalues (which are non-negative due to the positive semi-definite property of the covariance matrix).

Determinant and Inverse: If the determinant of the covariance matrix is zero, then it’s singular, which means it doesn’t have an inverse. In practical terms, this implies that some variables are linear combinations of others. If the determinant is non-zero, then the covariance matrix is invertible.

Rank: The rank of a covariance matrix tells us the number of linearly independent columns (or rows, because it’s symmetric). If some variables are perfect linear combinations of others, then the covariance matrix will be rank-deficient.

The orthogonality comes into play when we discuss the eigenvectors of the covariance matrix. If you’ve heard of Principal Component Analysis (PCA), it leverages this property. PCA finds the eigenvectors (principal components) of the data’s covariance matrix, and these eigenvectors are orthogonal to each other.

\(\rho\) (rho)#

Correlation

Note:

\(\sigma^2 \) (\(s_{ii}\))is the sample variance.

The length in the circular graph corresponds to \(\rho\).

\(\lambda ^{\frac{1}{2}}\) corresponds to the std of PC as \(\lambda\) is the variance of PC.

\(R^2\)#

Correlation (squared correlation)

Note: \(\gamma\) is the lower case for \(\Gamma\).

PCR (Principal Component Regression):#

Z#

Example#

Of course! Let’s use a very simple dataset as an example.

Data: Consider we have three data points in 2-dimensional space:

X1 = [1, 2]

X2 = [2, 3]

X3 = [3, 5]

We will treat these as column vectors, and let’s stack them into a matrix:

[1 2 3]

X = [2 3 5]

Step 1: Center the Data First, we’ll center the data by subtracting the mean of each variable.

Mean of first variable (rows): (1 + 2 + 3) / 3 = 2

Mean of second variable (columns): (2 + 3 + 5) / 3 = 10/3

Centered data:

[-1 0 1]

X' = [-2/3 1/3 5/3]

Step 2: Compute the Covariance Matrix The covariance matrix \( S \) for \( X' \) is:

sum(x1i * x1i) sum(x1i * x2i)

S = sum(x1i * x2i) sum(x2i * x2i)

For the small data set:

[2/3 4/3]

S = [4/3 14/3]

Step 3: Calculate Eigenvectors and Eigenvalues of the Covariance Matrix This is the most involved step. Here, we’re looking for vectors \( \Gamma \) and scalars \( \lambda \) such that \( S\Gamma = \lambda\Gamma \).

For our simple example, you’d typically use software or a mathematical method to find the eigenvectors and eigenvalues. Let’s assume (for the sake of simplicity) that:

Eigenvector 1 (associated with the largest eigenvalue λ1): Γ1 = [a, b]

Eigenvector 2 (associated with the smaller eigenvalue λ2): Γ2 = [c, d]

Step 4: Project Data onto Eigenvectors (Principal Components) To get the projection of the data onto the principal components, you multiply the transposed eigenvector matrix with the centered data.

[-1 0 1] [a c]

Y = [-2/3 1/3 5/3] * [b d]

The resulting matrix \( Y \) gives the scores of each original data point on the principal components.

In real scenarios with larger datasets and higher dimensions, you’d typically use software packages like Python’s scikit-learn or R’s built-in functions to do PCA. They handle the numerical details and optimizations behind the scenes.

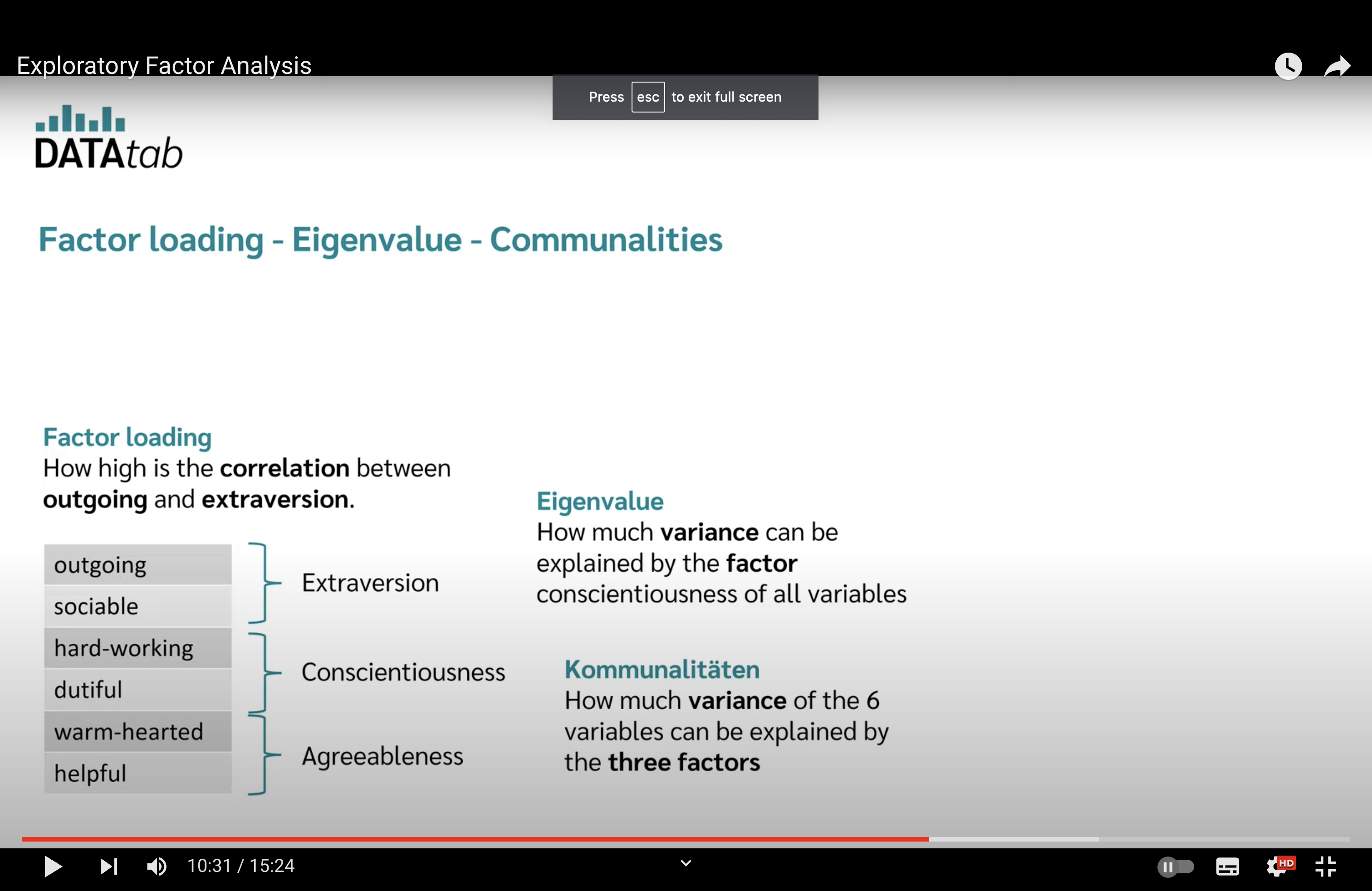

Communality#

In multivariate statistics, particularly in factor analysis, “communality” refers to the portion of the variance of a given variable that is accounted for by the common factors. In simpler terms, it’s the variance in a particular variable explained by the factors in a factor analysis.

Here’s a more detailed breakdown:

Total Variance: For each variable in a dataset, there’s a total amount of variance associated with that variable.

Unique Variance: A part of this total variance is unique to the variable, meaning it’s not shared with any other variables in the analysis. This unique variance could be due to unique factors or error.

Common Variance or Communality: The remaining variance (i.e., total variance minus unique variance) is the variance shared with other variables. This shared variance is what the factors in factor analysis aim to represent.

Mathematically, for a given variable: \( \text{Total Variance} = \text{Unique Variance} + \text{Communality} \)

In the context of factor analysis:

High communality for a variable indicates that a large portion of its variance is accounted for by the factors.

Low communality indicates that the factors do not explain a significant portion of the variance of that variable.

When you conduct factor analysis, you’re essentially trying to find underlying factors that account for the communalities among variables, which helps in reducing dimensionality and in understanding the underlying structure of the data.

Matrix Determinant#

To calculate the determinant of a (3 \times 3) matrix with elements (a, b, c; d, e, f; g, h, i), we can use the following formula: